Remember Jazzman Louis Armstrong? He Called Pres. Eisenhower out on Racism, Forever Changed History

Louis Armstrong is considered one of the most influential artists in jazz history, but there was a time where people in the country dubbed him as an “Uncle Tom” for his refusal to address the racist politics taking place on the civil rights era. However, he changed that perception in 1957, when he had enough and went off on President Eisenhower and Gov. Faubus while doing an interview.

Louis Armstrong playing the trumphet. | Photo: Wikimedia Commons Images

By the time the civil rights era exploded, Armstrong already had an established music career. He became the first African-American to do many things.

The first jazz musician to write an autobiography: “Swing That Music.” The first African-American to be featured in a major Hollywood movie, on Bing Crosby’s “Pennies from Heaven.” He also became the first African-American entertainer to host a nationally sponsored radio show in 1937, taking over Rudy Vallee's “Fleischmann's Yeast Show” for 12 weeks.

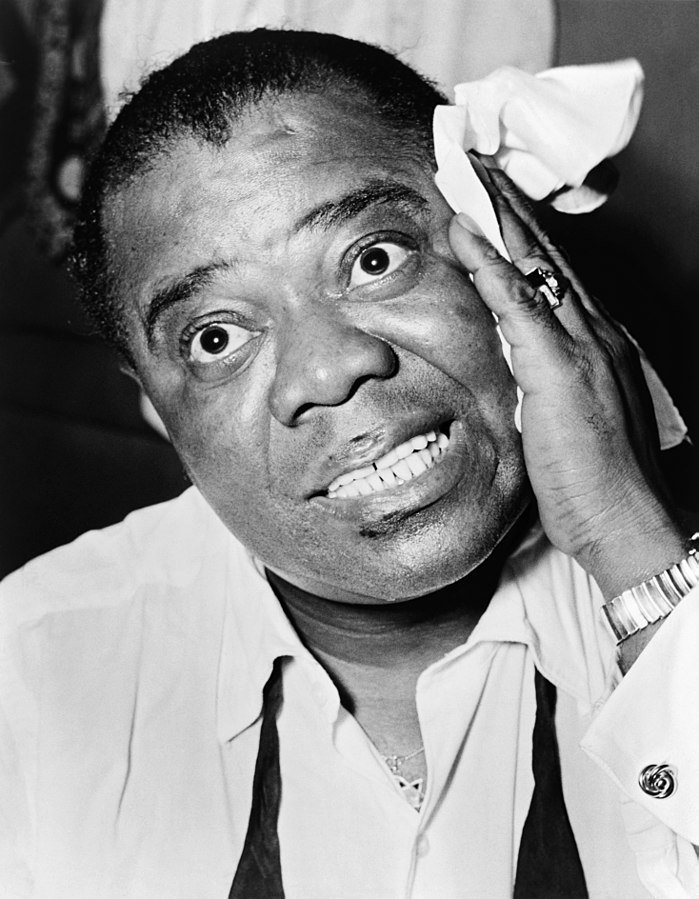

Portrait of jazz musician Louis Armstrong in 1953. | Photo: Wikimedia Commons Images

With the rise of bebop in the 1940s, many young jazz listeners started to consider Armstrong stage-persona and his style “old-fashioned.” It also didn’t help that he kept a soft demure, always smiling and refusing to address politics while African-Americans fought for their rights every day.

“I don’t get involved in politics,” he said once. “I just blow my horn.”

However, that changed in September 1957, amid the Little Rock Central High School integration crisis. Three years earlier, the U.S. Supreme Court issued the historic Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled all laws establishing segregated schools to be unconstitutional called for the desegregation of all schools throughout the country.

Louis Armstrong playing in Amsterdam. October, 1955. | Photo: Wikimedia Commons Images

In Little Rock, Arkansas, a plan to start a gradual integration was set to begin on the summer of 1957. That year, the NAACP had registered nine black students to attend Little Rock Central High, which had been an all-white school until then.

But in an unexpected change of events, governor Orval Faubus released the National Guard, preventing the students from entering the schools and stating they were trying to “preserve the peace.”

Facade of Central High School, Little Rock, Arkansas. | Photo: Wikimedia Commons Images

Armstrong was on tour with his All Stars band in Grand Forks, where he met then journalism student Larry Lubenow from the University of North Dakota. Lubenow had explicit instructions from his editor: to keep it about the music. But he had other plans.

Not knowing what to expect, the young journalist brought up Little Rock in his conversation with Armstrong, giving free rein to the musician to finally express his opinions. “It’s getting almost so bad a colored man hasn’t got any country,” a furious Mr. Armstrong told him.

Louis Armstrong plays trumpet with Joey Adams, president of the American Guild of Variety Artists Youth Fund. | Photo: Wikimedia Commons Images

He hurled profanities to President Eisenhower, referring to him as “two-faced” and saying he had “no guts” for allowing Gov. Faubus to out rule the law. When talking about the later, Armstrong stated he was a “no-good [expletive]” but since that word couldn’t be printed, he agreed with Lubenow on the epithet “uneducated plow boy.”

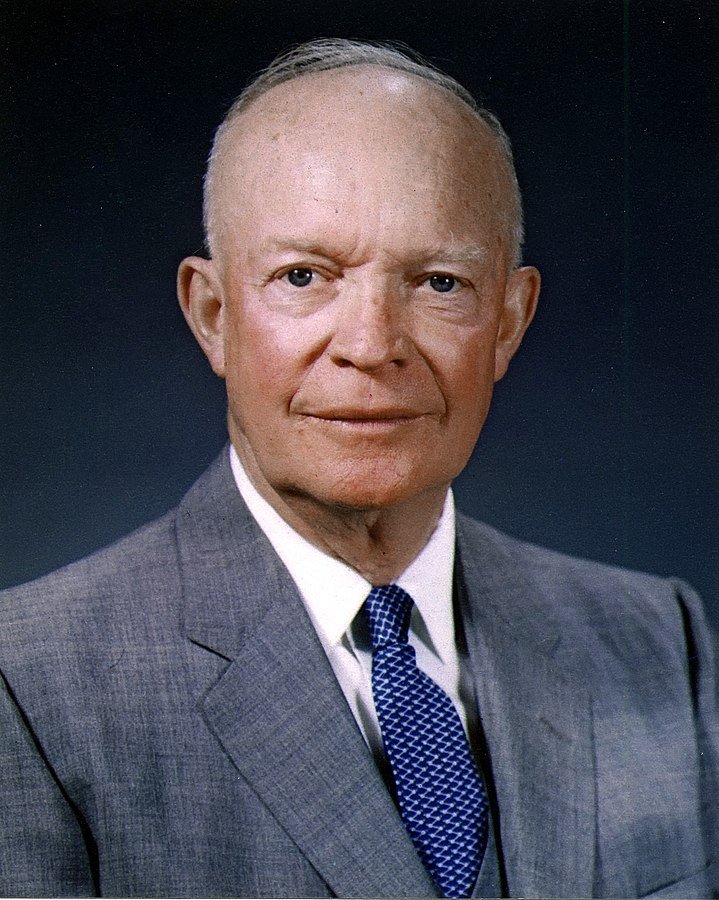

Dwight D. Eisenhower photo portrait. | Photo: Wikimedia Commons Images

Louis also allegedly went into an impromptu performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” changing its lyrics to insert more obscenities and prompting Velma Middleton, a vocalist who toured with him, to hush him up.

“The way they are treating my people in the South, the government can go to hell,” he said. “The people over there ask me what’s wrong with my country. What am I supposed to say?”

Faubus speaking to a crowd protesting the integration of Little Rock schools. | Photo: Wikimedia Commons Images

Armstrong's words traveled around the world. His road manager tried to backtrack his statement, saying he had been tricked, but the jazz legend had none of that. “I said what somebody should have said a long time ago,” he said on his concert in Montevideo, Minnesota, ending the show with a clean version of “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

He received criticism from both black and white folks. Some people called to boycott his concerts, and he faced threats of being left out of TV shows and other performances. However, his words affected.

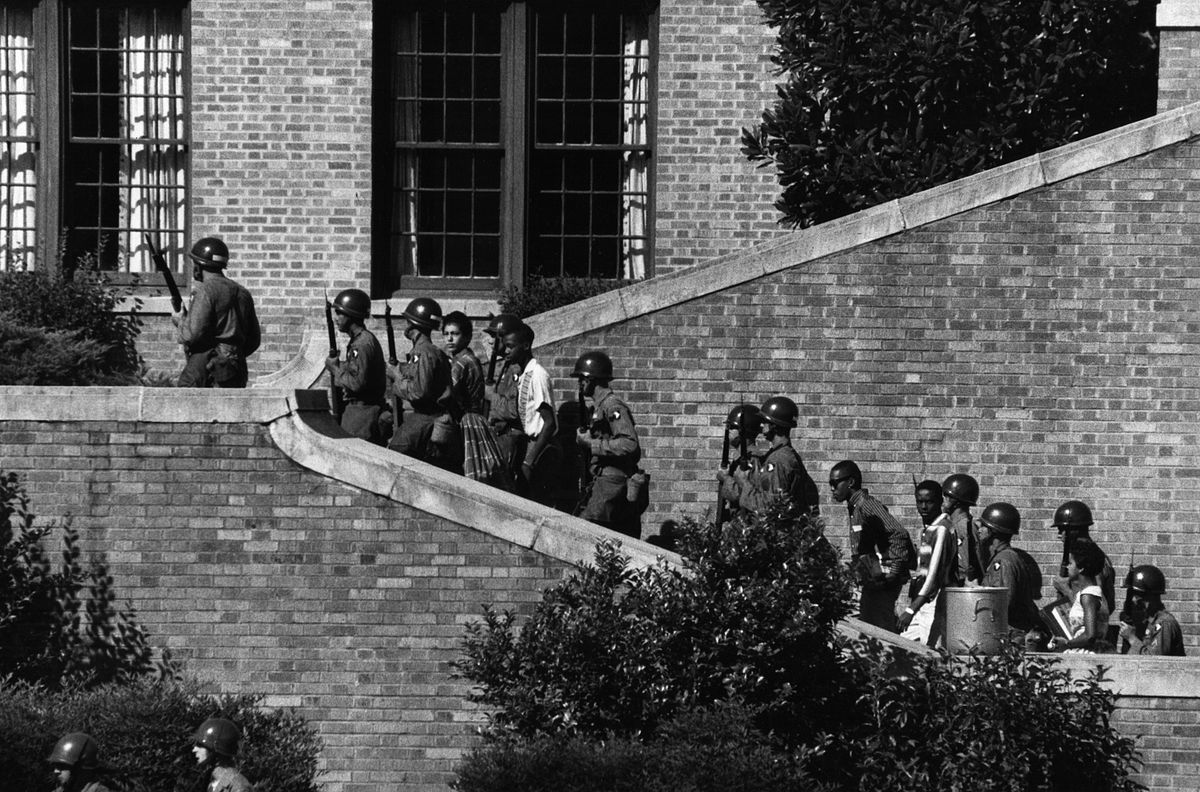

Soldiers escort the Little Rock Nine students into the all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Ark. | Photo: Wikimedia Commons Images

One week after the interview was published, President Eisenhower sent 1,200 paratroopers from the 101st Airborne into Little Rock. The next day, soldiers escorted the nine students into Central High School.

Mr. Armstrong had this message for the president: “God bless you.”