Ridley Scott Once Admitted to Being an Atheist — What to Know about His Faith and Beliefs

Ridley Scott's life's work has been an ongoing reflection on the human condition and man's relationship with an ultimate Creator, one which he sometimes portrays as benign, and other times as malignant.

Ridley Scott has produced a body of work that has made him one of the most influential directors of his generation. His films invariably delve into two fundamental themes: What is it to be human, and the ever bewildering relationship between creator and creation.

Scott, who has declared himself to be an atheist, is nevertheless fascinated with religion, belief, and the aforementioned relationship between man and his Creator -- a theme he returns to again and again.

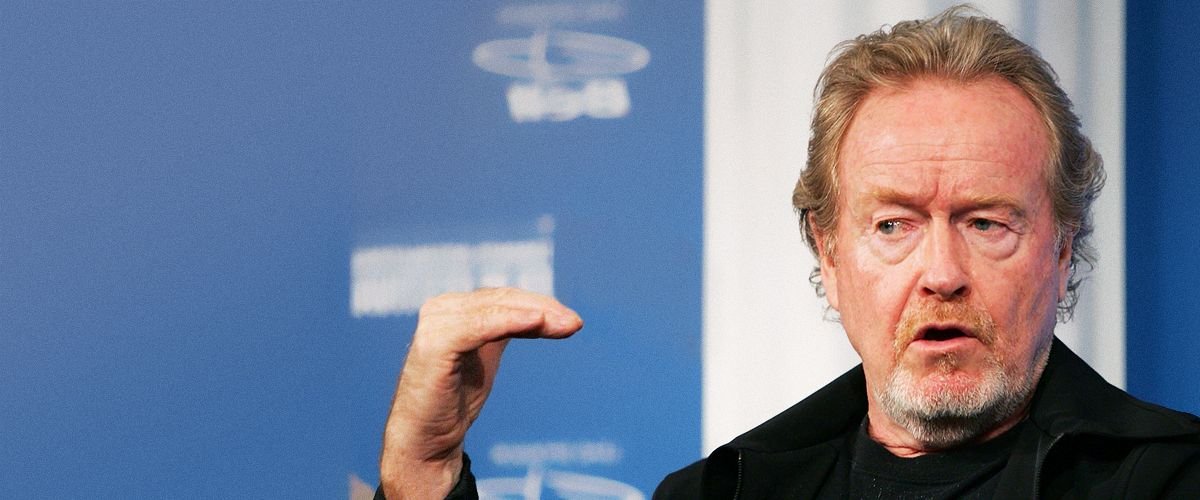

Sir Ridley Scott at his hand and footprint ceremony at TCL Chinese Theatre in 2017 in Hollywood | Source: Getty Images

THE SEEKING ATHEIST

It is curious that Scott has directed so many films that touch on the depths of faith, the need to believe, and the accountability of a Creator before his creations.

His 2005 blockbuster "Kingdom of Heaven" starring Orlando Bloom captured the essence (though perhaps not historically accurate) of the fall of Christian Jerusalem to Saladin, and the turn of the religious tide towards Islam in the 12th century, after the death of the Leper King, Baldwin IV.

The "creator," and the analysis of what a soul is, has been an underlying theme in many of Scott's greatest works

THE KINGDOM OF HEAVEN

Under the sadly shortlived King -- he died at 23 a victim of leprosy -- Jerusalem lived in a state of truce with Islam, a truce based on respect and mutual tolerance. Baldwin won that truce at swordpoint at the age of 16 and kept the fabled General Saladin at bay for the 10 years of his reign.

Scott's film captures the hunger for salvation and forgiveness of sins that led so many to take up the cross and journey through half the known world to Jerusalem -- and their disillusionment, not with their faith, but with the men who represented God on earth.

EXODUS

In 2014, he returned once again to one of the core stories of the Judean-base religions: the exodus of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt in the film "Exodus: Gods and Kings." Scott commented on his choice of the film:

"I’m an atheist, which is actually good, because I’ve got to convince myself the story works."

The story "works," and has worked for millennia, not so much as a historical account as an ode to freedom, and has been the rallying cry of oppressed people everywhere: "Let my people go."

In Scott's hands, critics complained that the religious aspect was neglected, and although visually stunning, the film lacked gravitas. It didn't help that he cast God as a child -- an additional comment on Scott's ongoing thesis about the responsibility and morality of creators.

THE CREATOR COVENANT

The "creator" and the analysis of what a soul is, has been an underlying theme in many of Scott's greatest works. In "Blade Runner," the replicants, synthetic humans, return to death to seek out their creator and to beg for mercy, for life.

In the final scene, the dying replicant Roy Batty chooses to deliver the mercy he did not receive, saving the life of the man sent to destroy him, Rick Deckard. As Batty's life runs out, he defines the cruelty of mortality. He says:

"I've seen things you people wouldn't believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die."

Scott returns to the morality of creation and the question of mortality again and again in his sequels to the 1979 sci-fi cult movie "Alien," "Prometheus," and "Alien: Covenant."

It is easy to see why Scott angers the establishment. In "Prometheus," the deeply religious Doctor Elizabeth Shaw discovers that the longed-for Creators are not only less than perfect but outright malignant and determined to destroy their creation, the human race.

In "Alien: Covenant," humanity's own creation, the perfect android "David," becomes humanity's nemesis as he himself spawns an unholy race of alien creatures whose sole drive is to kill.

"David" is the quintessential perfect creation, destined to become a destroyer, whereas Batty is the flawed, compassionate creation destined for a brief existence made rich by love and a hunger for beauty.

Is Scott an atheist? In the last scene of "The Gladiator," his hero Maximus dies. He is swept through a door into an afterlife in which he is greeted by his beloved wife and son, in a world of peace and beauty.

It is a paradise Batty would have welcomed with all of his synthetic soul, and one "David" would have rejected. Ridley Scott's idea of the Kingdom of Heaven is one in which all good hearts are welcomed and find peace. Scott is preaching humanism, and his audience is his congregation.