How The Humankind Survived — A Brief History of Vaccines

Since the dawn of civilization, humankind has been fighting ceaselessly to survive—countries, borders, resources … the list goes on and on. However, there’s one battle that isn't getting talked about enough, and that’s our battle against diseases.

Humankind had been struggling with diseases for centuries, and they had claimed the lives of so many before us—and potentially those after us as well. It is an endless battle, but with the advance in medicine and technology, we were able to have a better understanding of our mortal enemies and devise plans to counter them.

One of them is vaccination, a means to prevent diseases altogether.

We have come a long way when it comes to vaccination and disease prevention—but have you wondered how it all started? And the little victories and triumphs we had in this long battle against our mortal enemies? It wasn’t easy, but we found the way.

Sign encouraging the vaccination of children, Haiti, circa 1990s | Source: Getty Images

While modern vaccination is a rather modern thing, the idea of disease prevention through inoculation had been around for a long time. Some even said that it could be traced back to ancient China, hundreds of years ago.

Instead of injections like what we have today, they used a rather peculiar method as a means to inoculate the masses.

It started with smallpox, one of the deadliest diseases known to humankind.

Smallpox

The reason why you might not have heard of smallpox is that we managed to eradicate that altogether a few decades ago—and we will get to that later in this article.

Smallpox was a strong infectious skin disease that comes with a fever and a distinctive, progressive skin rash. According to CDC, about three out of ten patients who got smallpox would die from the disease—essentially a 30% death rate, which is highly alarming.

And considering how contagious it was, it became a problem for countries all around the world for centuries. However, the ancient Chinese had a peculiar way to deal with that.

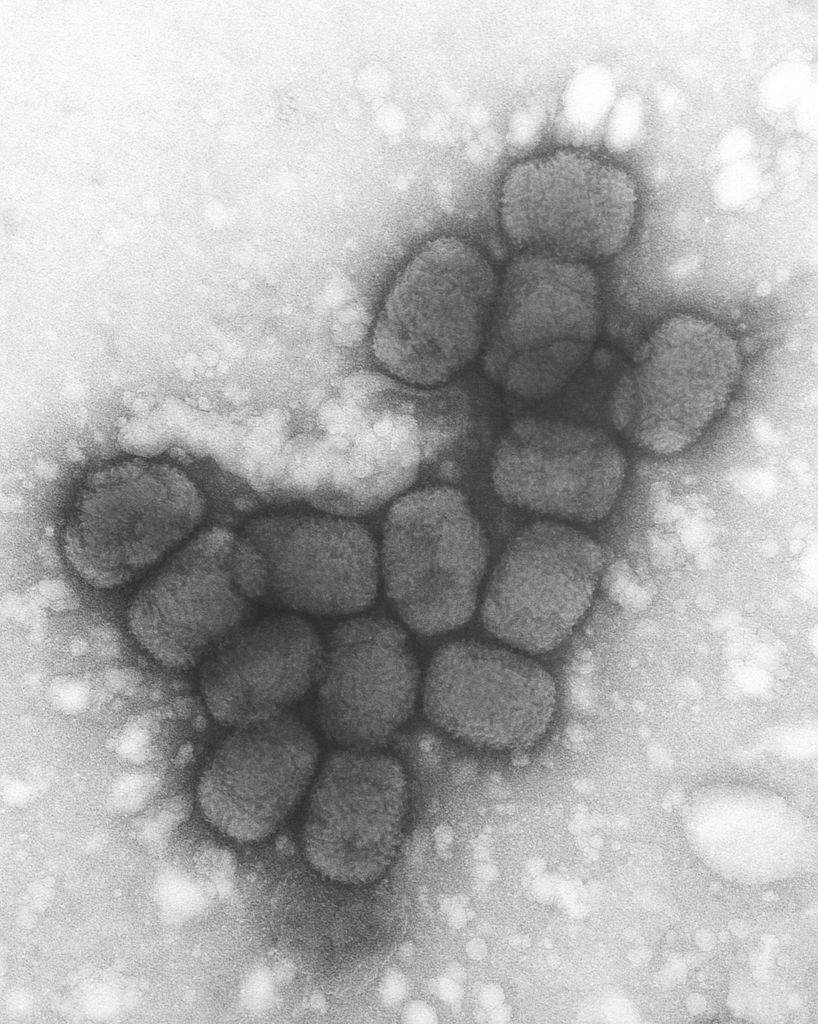

A transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of smallpox viruses using a negative stain technique, 1975 | Source: Getty Images

Early Chinese Inoculation

Also known as variolation, the way the ancient Chinese inoculate the masses from smallpox was by scratching matter from a smallpox sore into a healthy person's arm.

Sounds rather strange, isn't it? But it worked. And if you understand the theory behind vaccines, such practice isn't really that far from our more stable and reliable modern variants.

Let's take a look, shall we?

Soviet poster advocating smallpox vaccination, circa 1920s | Source: Getty Images

How Vaccines Work

Let's take the flu as an example—people suffered dearly from it during their first time (remember your first flu?), but as you get older and older … sure, you might get sick again, but you won't feel as bad normally unless you have other underlying conditions. So why's that?

Immunity, that's the key—for minor viruses, every time you get sick, your body started building immunity against that virus. According to Science Direct, this is what they had to say about adaptive immunity:

This provides a specific immune response directed at an invading pathogen. Following exposure to a foreign organism there is an initial EFFECTOR RESPONSE that eliminates or neutralizes a pathogen. Later re-exposure to the same foreign organism induces a MEMORY RESPONSE with a more rapid immune reaction that eliminates the pathogen and prevents disease. This response is found only in vertebrates.

It has been known from historical times that a person who has recovered from an infectious disease, e.g. smallpox, is most unlikely to suffer from it again – even when exposed maximally – although he would remain susceptible to other infections.

Penicillin manufacturer at Charles Pfizer factory testing cultures | Source: Getty Images

Vaccines work on a similar theory, and here's the British Society for Immunology's explanation on how it works:

Vaccines contain a harmless form of the bacteria or virus that causes the disease you are being immunised against. The bacteria or virus will be killed, greatly weakened, or broken down into small parts before use in the vaccine so that they can trigger an immune response without making you sick. Your immune system will still attack the harmless form of bacteria or virus from the vaccine and will produce antibodies to fight it off. The immune system then keeps a memory of the disease, so if a vaccinated person encounters the disease years later, their immune system is ready to fight it off and prevent an infection from developing.

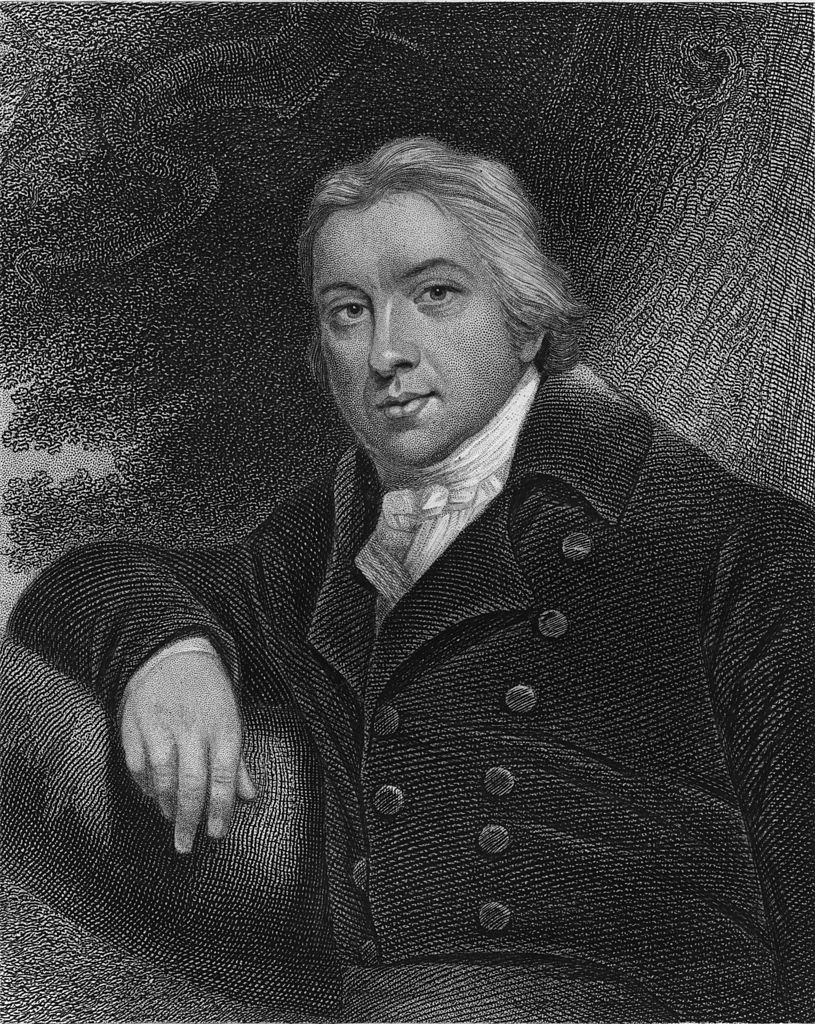

So how did we discover that? How did we understand that we could weaken the bacteria or virus? That brings us to Edward Jenner, whom many considered the father of immunology.

Packing ampoules of the BCG (Bacillus Calmette-Gurin) vaccine for tuberculosis developed by the Pasteur Institute in Paris, France in 1931 | Source: Getty Images

Edward Jenner and Smallpox

While it was known that smallpox survivors were unlikely to suffer from the disease again, there was still a high risk—30% death rate is no joke.

However, it was Edward Jenner who discovered that dairymaids who suffered from cowpox, a much weaker version of smallpox, were much less likely to suffer from smallpox. He began to notice the connection and dove deeper into the whole idea. According to the US National Library of Medicine, this was how Jenner first applied his theory to his patients.

In May 1796, Edward Jenner found a young dairymaid, Sarah Nelms, who had fresh cowpox lesions on her hands and arms. On May 14, 1796, using matter from Nelms' lesions, he inoculated an 8-year-old boy, James Phipps. Subsequently, the boy developed mild fever and discomfort in the axillae. Nine days after the procedure he felt cold and had lost his appetite, but on the next day he was much better. In July 1796, Jenner inoculated the boy again, this time with matter from a fresh smallpox lesion. No disease developed, and Jenner concluded that protection was complete.

Despite the groundbreaking discovery, we still had a long way to go before eradicating smallpox.

British physician Edward Jenner (1749 - 1823) who discovered the vaccine against smallpox | Source: Getty Images

Eradicating Smallpox

Inoculation against smallpox was finally discovered in the Western world in the late 18th century, but it'd take nearly two more centuries to fully eradicate smallpox.

Back in the 19th century, we didn't have a sufficient understanding of viruses and bacterias, so even though a means of inoculation had been discovered, it wasn't always effective—and it wasn't until the late 19th century that we discovered the fact that vaccination did not confer lifelong immunity, and that revaccination was necessary in order to prevent it altogether.

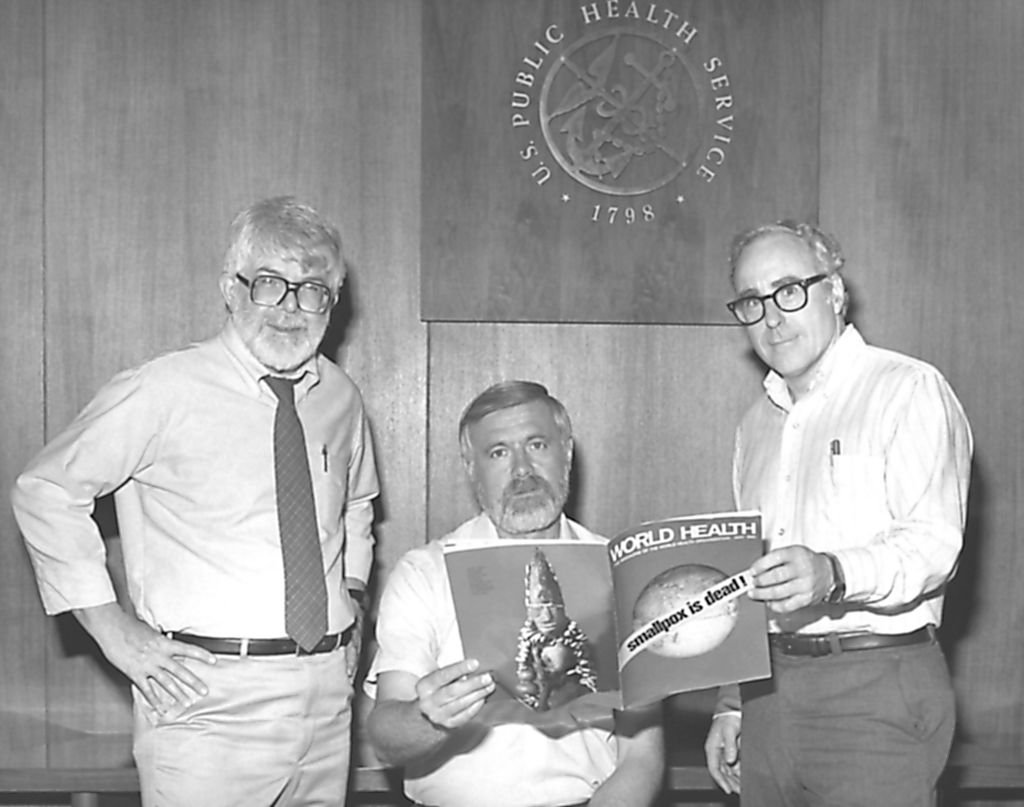

In the 20th century, under the coordinated efforts of the World Health Organization, a global campaign was launched to vaccinate against smallpox.

The result? We managed to eradicate smallpox in 1980—a once deadly threat to humankind was no more.

Three former directors of the Global Smallpox Eradication Program, Dr J. Donald Millar, Dr William H. Foege and Dr J. Michael Lane, holding world Health magazine, 1980. Image courtesy Centers for Disease Control (CDC) | Source: Getty Images

Other Vaccines

Of course, smallpox wasn't the only deadly disease we had to deal with. Measles, polio, yellow fever … there are still many diseases that we have yet to eradicate. However, compared to where we were a hundred years ago, we have made some tremendous progress.

As for measles, while it has been mostly eradicated in developed countries, developing countries are still suffering from it; as for polio, five out of six WHO regions are now certified wild poliovirus free, which is some remarkable progress made within just a hundred years.

We even have vaccines against lung cancer! Can you believe that? In Cuba, experts managed to develop a vaccine against lung cancer by devising a means to "starve" the cancer cells and thus, prolonging tumor stabilization and improve the overall survival rate.

A child is injected with a vaccine against paralytic poliomyelitis, 1956 | Source: Getty Images

The battle against diseases is a long and hard one, but we managed to overcome obstacles after obstacles over the last hundred years. While we might not be able to eradicate every single disease in the world, every life saved is a small victory that's worth celebrating.

What do you think about this article? If you enjoyed reading it, why not share it with your friends and family? Until next time!