'It's a True Miracle': Woman Who Survived Rare Cancer Becomes Mom to Twins – Her Story Moves Everyone

A rare and aggressive form of breast cancer threatens fertility in many young women. It's also notoriously hard to treat. Yet, with quick intervention and modern treatment, one survivor beat the odds, stunning even seasoned doctors.

The phrase "It's a true miracle" isn't one Shelly Battista uses lightly. After undergoing aggressive treatment that took both her breasts and ovaries, she was told she'd never conceive naturally again. But against all odds, she welcomed identical twins into the world.

Shelly Battista with her husband and oldest daughter at a breast cancer awareness event, dated January 12, 2023 | Source: Facebook/northwesternmedicine

At the heart of Shelly's journey is a rare cancer with limited treatment options and even fewer guarantees. Yet, through groundbreaking medical advancements and swift, life-changing decisions made at her most vulnerable moment, she now shares her home with three children.

A doctor holds Shelly Battista's newborn twins at the hospital, dated January 12, 2023 | Source: Facebook/northwesternmedicine

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer and Its Impact on Fertility

For women in their 30s, a breast cancer diagnosis often brings two parallel crises: the immediate threat to life and the quiet, rapid erosion of fertility.

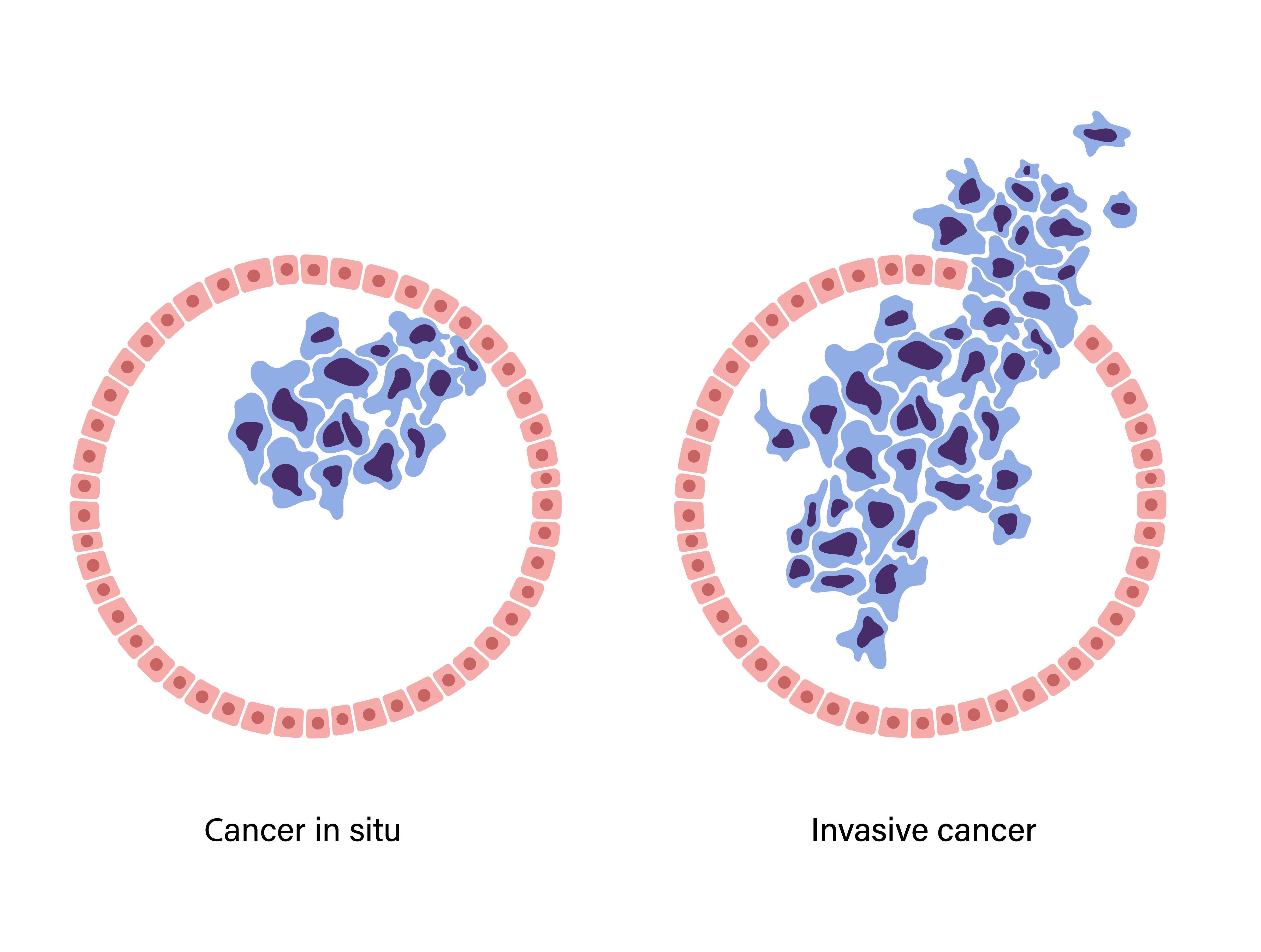

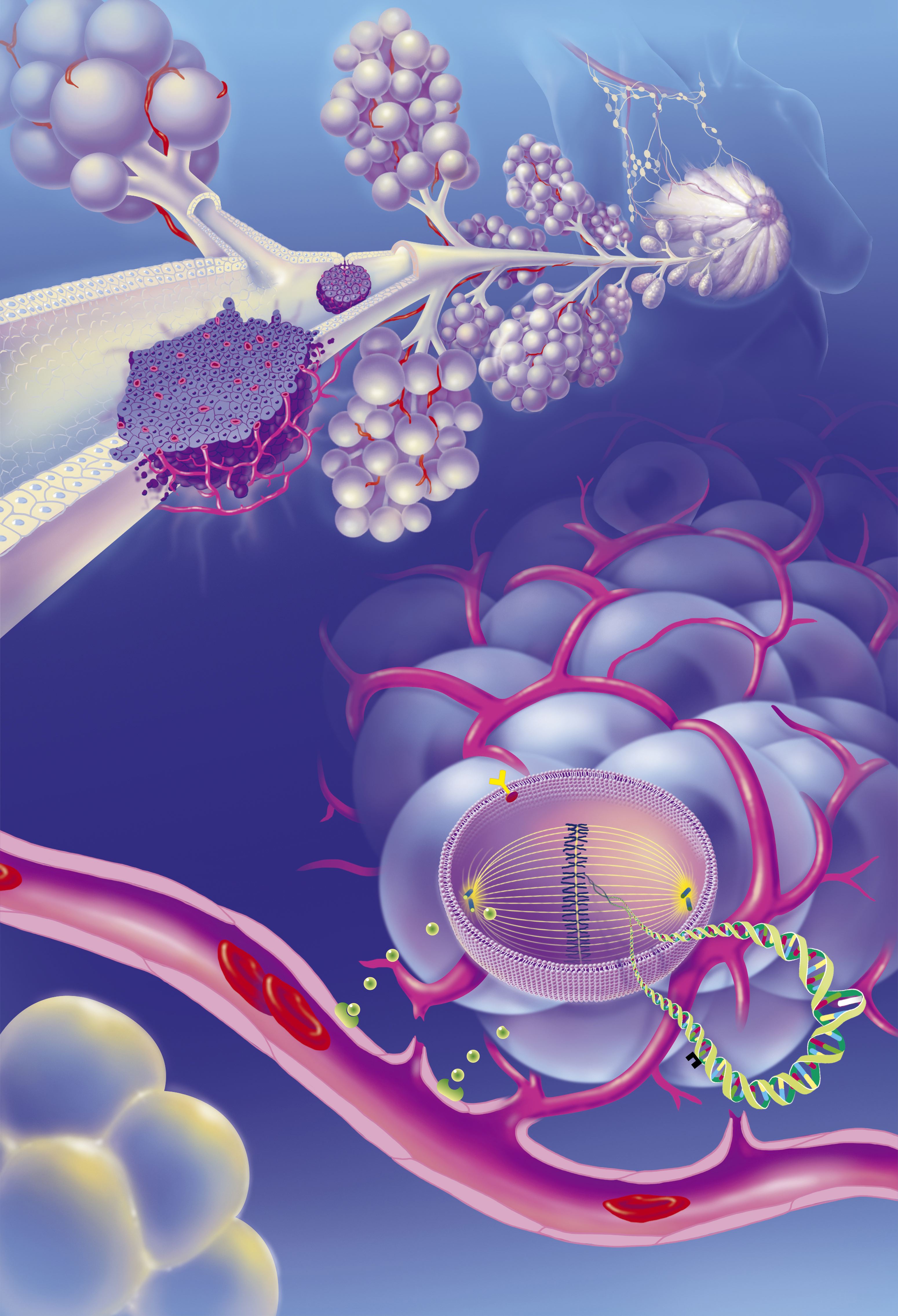

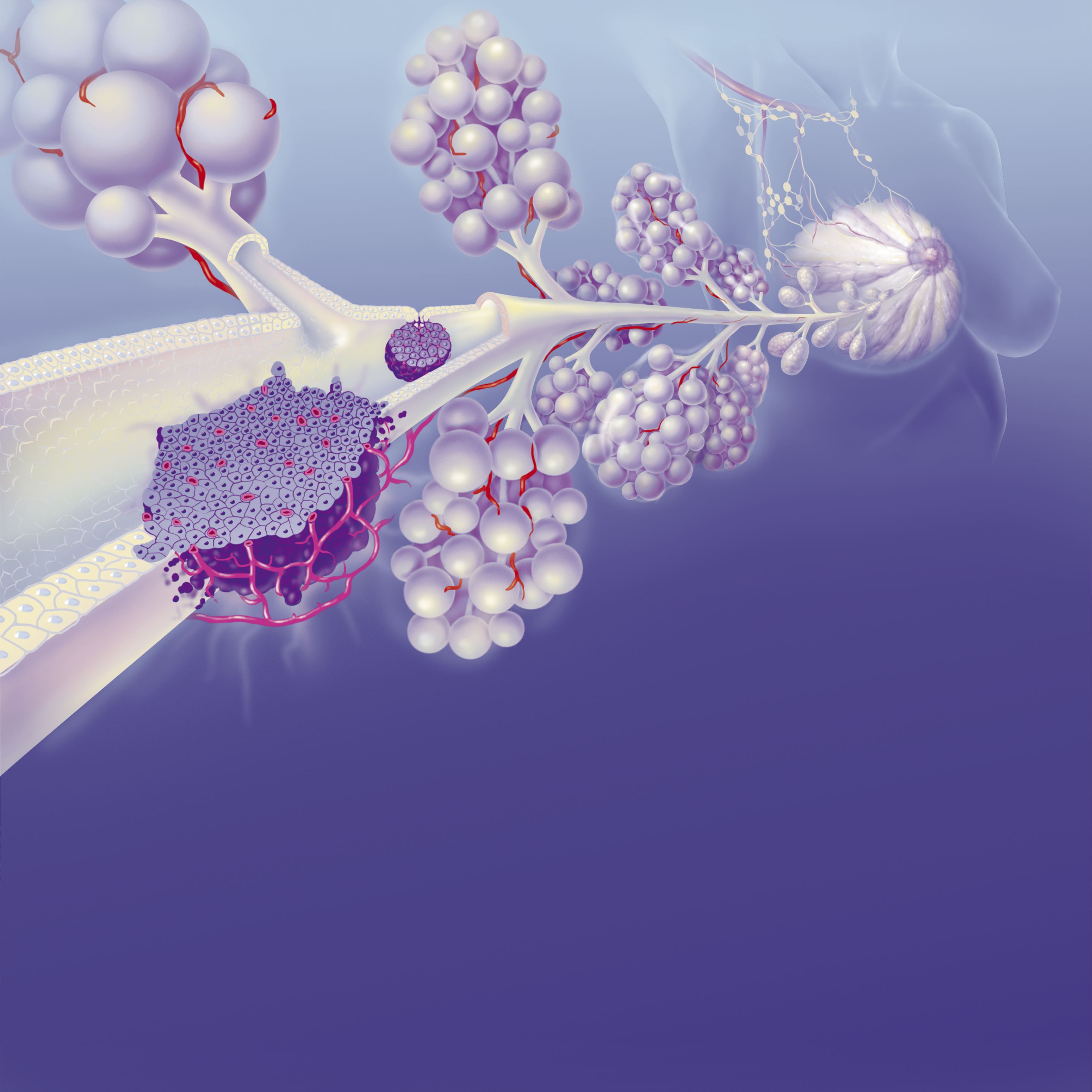

Triple-negative breast cancer, or TNBC, is a rare but aggressive form of the disease. It accounts for a small percentage of breast cancer cases but carries disproportionate risk, especially for younger patients. TNBC lacks the three receptors — estrogen, progesterone, and Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor, also known as HER2 — that most treatments target to block tumor growth.

Visual representation of how breast cancer cells form and spread within breast tissue | Source: Getty Images

Without those biological entry points, chemotherapy becomes the only effective course of action. Chemotherapy, though necessary, is harsh. In women of reproductive age, it can quickly damage the ovaries, reducing hormone production and egg reserves.

For some, this results in temporary menopause; for others, the loss of fertility is permanent. The impact is more than physical — it removes future options before a patient has even had time to process her diagnosis.

A woman pointing to a pink ribbon pinned to her chest, symbolizing breast cancer awareness | Source: Getty Images

Adding to the complexity is the association of TNBC with inherited gene mutations, particularly those affecting the BRCA1 (BReast CAncer gene 1) and BRCA2 (BReast CAncer gene 2). These mutations not only increase the likelihood of breast cancer but also sharply raise the risk of ovarian cancer.

For patients who test positive, doctors often recommend preventive surgery to remove the ovaries and fallopian tubes, further narrowing the possibility of future pregnancy. Even so, there is a sliver of time, a fragile, high-stakes window in which fertility can be preserved.

A woman placing her hands over her chest, representing a breast health awareness concept | Source: Getty Images

If caught early enough, and if a patient is well enough to proceed, doctors can begin hormone stimulation to retrieve eggs for freezing. Embryos can also be created using a partner's sperm or a donor's sperm. But this process must be completed before chemotherapy starts. In many cases, that means beginning within days of diagnosis.

Under ordinary conditions, fertility preservation is a tightly choreographed process: daily hormone injections, ultrasound monitoring, bloodwork, egg retrieval, and embryo freezing. But in the context of a cancer diagnosis, that choreography becomes a sprint.

Medical illustration showing invasive and in situ ductal carcinomas. The image traces a zoom from the mammary gland to the milk duct, highlighting tumor locations, glandular structure, and axillary lymph nodes | Source: Getty Images

Delaying chemotherapy increases medical risk. Forgoing preservation can mean giving up the chance to have biological children. The balance between those choices has become one of the defining dilemmas of modern oncology.

Shelly faced that dilemma before the full weight of her diagnosis had even landed. She was 34, still adjusting to life as a first-time mother, and suddenly faced a decision no new parent should ever have to make: should she begin fighting for her life or first try to save the chance to build the family she had always imagined?

Medical illustration showing invasive and in situ ductal carcinomas. The image zooms in from the mammary gland to the milk duct, highlighting tumor locations, glandular structure, and axillary lymph nodes. Two cancerous tumors are shown on the main milk duct: an invasive ductal carcinoma (left) and a carcinoma in situ | Source: Getty Images

A Missed Signal, a Rushed Decision

Shelly had barely returned to the rhythms of working motherhood when something changed. In February 2020, while pumping at the office, she felt a lump in her breast. She chalked it up to a clogged duct, common among nursing mothers, and continued.

But the lump stayed. And as weeks passed, so did the window for early intervention. Shelly had no family history of breast cancer. No known genetic risk. And with the COVID-19 pandemic disrupting routine appointments, her evaluation was delayed.

A woman clutching her chest, indicating sudden chest pain—a potential symptom requiring medical evaluation | Source: Getty Images

It wasn't until May, three months after she first felt the lump, that she was formally diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer. She was caring for a six-month-old and suddenly facing a type of cancer known to move fast and hit hard. "We were just starting our life together," her husband, Robert Battista, later recalled. "And we get this shocking news."

Within days, genetic testing revealed something more: Shelly carried mutations that sharply increased her risk for ovarian cancer. That finding meant her treatment plan wouldn't stop at chemotherapy. It would eventually include a double mastectomy and the removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes, procedures that would leave her unable to conceive naturally.

Shelly Battista and Robert beam with happiness while holding their newborn twins, dated March 20, 2023 | Source: Youtube/@TODAY

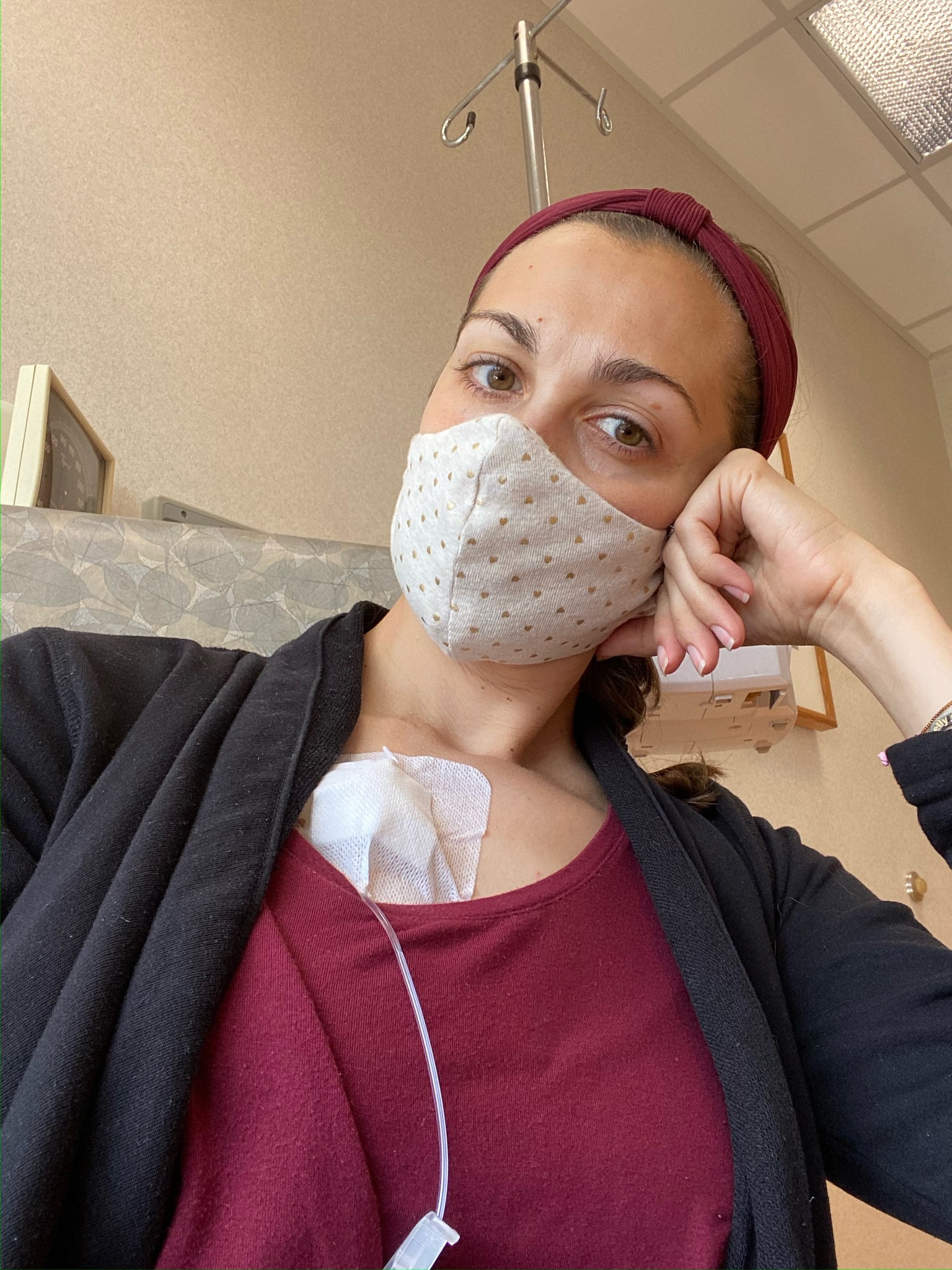

But before any of it began, there was one step left to take if it wasn't already too late. Shelly was referred to Dr. Kara Goldman, a reproductive endocrinologist at Northwestern Medicine. With little time to spare, Shelly started hormone injections just two days after her diagnosis.

Over the next two weeks, she underwent the full cycle of fertility preservation: daily injections, bloodwork, and ultrasounds to stimulate and monitor her ovaries. It was physically demanding and emotionally disorienting. She was preparing for cancer treatment while trying to secure the future it threatened to erase.

Shelly and Robert Battista smile as they hold their newborn twin daughters, dated March 20, 2023 | Source: Youtube/@TODAY

At the end of those two weeks, doctors retrieved and froze eight embryos. Even though they wouldn't be used right away, they represented a possibility, one final decision made before she began the treatments that would take away her ability to conceive naturally.

Chemotherapy, Surgery, and the End of Natural Fertility

Shelly's treatment began immediately after her fertility preservation cycle was complete. The first phase: 12 rounds of chemotherapy, each one aimed at slowing the cancer's spread, each one pushing her body further from the life it had just created months earlier.

Shelly Battista, dated March 20, 2023 | Source: Youtube/@TODAY

As the weeks went on, she began preparing for surgery. A double mastectomy was the next step, standard for patients with triple-negative breast cancer, especially those with BRCA gene mutations. Shelly didn't hesitate as the priority was survival.

But the emotional weight of what was being taken from her — her breasts, her strength, and soon, her reproductive future — was never far behind. The cancer responded to treatment, but doctors remained concerned about her elevated genetic risk for ovarian cancer.

Shelly Battista watches the screen during a routine pregnancy ultrasound, dated January 12, 2023 | Source: Facebook/northwesternmedicine

To protect her long-term, they advised a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy: the surgical removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes. By the time she completed treatment, Shelly no longer had the organs required to conceive a child.

Her uterus remained intact, but her ovaries, once stimulated to produce the embryos she'd frozen just weeks earlier, were gone. However, she'd done everything she could to preserve what was possible. The embryos were waiting, and she was cancer-free.

Shelly Battista and her oldest daughter pose outside on her 2nd birthday, dated January 12, 2023 | Source: Facebook/northwesternmedicine

Rebuilding Possibility: Pregnancy Without Ovaries

One year after completing treatment, Shelly was ready to try. "The ovaries and the uterus function very independently of each other," explained Dr. Goldman, Shelly's fertility specialist at Northwestern Medicine. In cases like this, hormone replacement therapy can prepare the uterus for pregnancy.

"Because she did not have ovaries producing hormones," Dr. Goldman added, "we were able to provide her the hormones necessary for pregnancy."

Shelly Battista during a hospital visit, dated January 12, 2023 | Source: Facebook/northwesternmedicine

The first two embryo transfers didn't work. Each failed attempt brought disappointment but not defeat. On the third try, Shelly received a call directly from Dr. Goldman. The embryo had implanted, and she was pregnant. "We were both ecstatic and crying and yelling," Shelly recalled.

For Robert, the news was more than just relief. "It was just awesome. We were going to have another kid, Shelly's healthy, everything was behind us at that point," he stated. But what came next was something they hadn't planned for.

Shelly Battista and her baby wear matching "Shelly Strong" bracelets, dated January 12, 2023 | Source: Facebook/northwesternmedicine

A Rare Twin Pregnancy and the Day Everything Came Full Circle

Following a successful embryo transfer, Shelly returned for a routine ultrasound. The transfer had involved one embryo, selected from the eight frozen before her chemotherapy. But the scan revealed an unexpected result: identical twins.

Fetal ultrasound image from Shelly Battista's pregnancy, taken during a medical exam, dated January 12, 2023 | Source: Facebook/northwesternmedicine

The embryo had divided after implantation, a phenomenon that occurs in approximately one percent of cases, according to Dr. Goldman. There was no intervention, and no fertility technique designed to increase the odds of multiples. It had happened on its own.

Despite her medical history, her pregnancy went smoothly. Her uterus responded well to the carefully timed hormone support. No complications. No setbacks. Only waiting and counting down the days. Shelly was scheduled for induction at Northwestern Medicine Prentice Women's Hospital.

Shelly Battista's daughter, Emelia, stands beside her newborn twin sisters, dated January 12, 2023 | Source: Facebook/northwesternmedicine

The date set was December 9, 2022, exactly two years after she had completed treatment and been declared cancer-free. The medical team had not planned that coincidence. But for the new parents, it added a personal significance to a clinical milestone. Their daughters, Nina and Margot, were born that day.

"Despite a breast cancer diagnosis, chemotherapy, and losing both ovaries, Shelly's dream of having three children came true," Dr. Goldman later stated. "One perfect embryo, frozen urgently before chemotherapy, became two beautiful baby girls."

Shelly Battista’s newborn twins sleeping side by side, dated January 12, 2023 | Source: Facebook/northwesternmedicine

"It's a true miracle," Shelly said. "We have two babies, exactly two years cancer-free. My heart is very full." Months after the twins' birth, Shelly appeared on the "Today Show," where she reflected on life after cancer and childbirth.

"Lots of laughs, lots of cries and lots of laundry," she described her day-to-day life. "It's chaotic, but it's perfect." At the time, she and Robert were adjusting to life with three children, Emelia, Nina, and Margot. The story of their family's journey drew widespread response online.

On Instagram, users flooded the comments section with support and emotion. "Congrats! What a beautiful story. You are a strong mama," one person wrote.

Another commented, "Congratulations…what a blessing," while one reacted with, "Awesome!!!" Another added, "What a wonderful story!!" One called her a "warrior mama" and added, "Congratulations!"

The information in this article is not intended or implied to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. All content, including text, and images contained on news.AmoMama.com, or available through news.AmoMama.com is for general information purposes only. news.AmoMama.com does not take responsibility for any action taken as a result of reading this article. Before undertaking any course of treatment please consult with your healthcare provider.